What does it mean to talk of a 'Nigerian Footballing Identity', and should we seek a return to the wing-based 4-4-2 the Super Eagles once employed?

ANALYSIS

By Okeowo Destiny

By Okeowo Destiny

If you had woken up from a two-year coma on the 11th of July, 2010 colour-blind (improbable, yes, but humour me here) and watched the final of the World Cup in South Africa, you would have been hard pressed to identify who Spain were playing against.

The team that played in orange was as far from the template of Rinus Michel’s Ajax team of the ‘70s as light is from darkness. It was Anakin Skywalker becoming Darth Vader: Bert van Maarwijk had taken the Netherlands over to the Dark Side in a bid to achieve victory. It backfired spectacularly.

Every nation has some semblance of a footballing identity, its own popular idealistic interpretation of how the beautiful game ought to be played. For the Dutch, it is Total Voetbal: a possession-based style employing dizzying fluidity of movement and a 4-3-3.

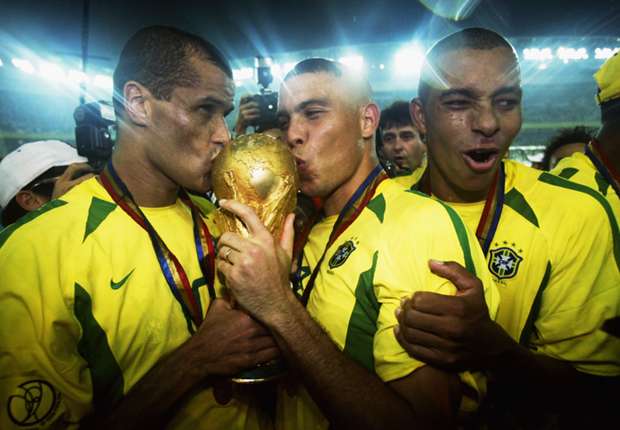

For Brazil, it is joga bonita: the defiance of structure and discipline in favour of blatant expressionism. Often, this view contrasts with the reality on the ground: it was a much more pragmatic Brazil side, for example, that claimed the world title in 2002.

Brazil 2002 | Even Joga Bonita had its exceptions

Walk into a Nigerian bar, buy a few drinks and subtly turn the conversation to the Super Eagles.

Chances are, before long someone will go off on a rant about the need to return to ‘wing play’ or how the national team no longer ‘uses the flanks’.

It is not hard to understand why.

Nigeria debuted on the world stage playing a 4-4-2 with tremendous width, and has had a long love affair with wingers going back to Adokiye Amiesimaka and ‘Mathematical’ Segun Odegbami, who remains Nigeria’s all-time record holder for goals.

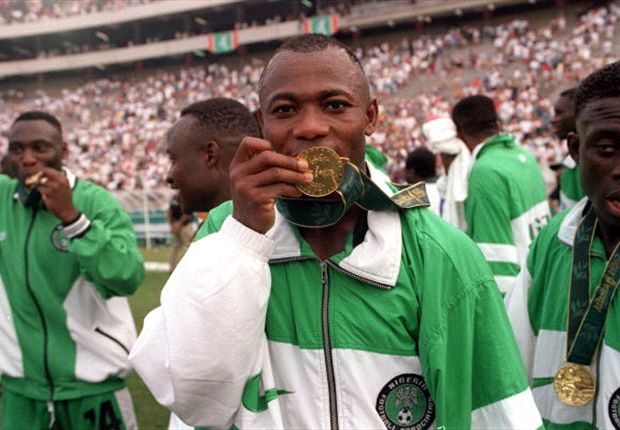

The great team of the mid-90s also benefited from superlative wingers in Finidi George, Emmanuel Amuneke and, to a later and lesser extent, Tijani Babangida.

So, what precipitated the shift away from a direct, attacking style based around width? Why is this golden age remembered with such fondness, but is no longer the de facto approach of the Super Eagles?

Amuneke | A Lamented Passing

Well, to begin with, it is impossible to ignore the decline of the 4-4-2 in the 2000s.

As football became more preoccupied with ball retention, having two players in the middle of the park quickly became inadequate as most teams started to field three central midfielders. Chelsea manager Jose Mourinho, in his first spell at Stamford Bridge between 2004 and 2006, famously highlighted the weakness of the 4-4-2, which was still somewhat prevalent in the English Premier League at the time.

Look, if I have a triangle in midfield – Claude Makelele and two others just in front – I will always have an advantage against a pure 4-4-2 where the central midfielders are side by side. That’s because I will always have an extra man. It starts with Makelele, who is between the lines. If nobody comes to him he can see the whole pitch and has time. If he gets closed down it means one of the other two central midfielders is open. If they are closed down and the other team’s wingers come inside to help, it means there is space now for us on the flank, either for our own wingers or for our full-backs. There is nothing a pure 4-4-2 can do to stop things.

This was a headache for successive managers of the Super Eagles: being undermanned in midfield.

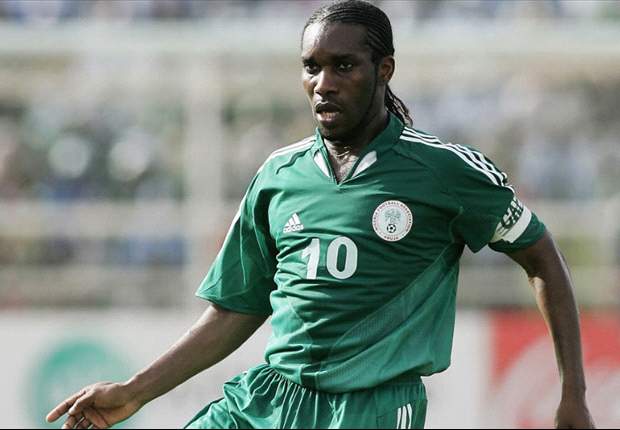

A case in point was discussed in a previous article; another was at the Nations Cup in 2000. Again, Jo Bonfrere repeated the error that led to Bora Milutinovic’s downfall two years earlier: he fielded a midfield pairing of Jay Jay Okocha and Sunday Oliseh in the opening game. The Super Eagles bludgeoned Tunisia 4-2, and the scoreline tells you all you need to know. Great attacking flair, defensive insecurity.

In fairness to Bonfrere, it was a hard choice.

Okocha was the team’s best player, but fitting him into the team tactically was a headache in a 4-4-2. It was no coincidence that, with Okocha suspended for the semi final against South Africa, the Super Eagles produced their most nerveless, composed performance of the tournament, winning 2-0 with a midfield base of Oliseh and Mutiu Adepoju. Sure enough, Okocha was back for the final against arch enemy Cameroon, shoehorned into the team in a very narrow left-sided midfield role. Bonfrere’s compromise ensured Nigeria were not dominated in midfield, but it also meant no one attacked the space behind Geremi Njitap. Naturally, Jay-Jay went where he pleased.

For the purpose of competing against the very best, it was clear that pairing Oliseh with Okocha would prove inadequate. So then, the obvious answer would be that the shift was precipitated by the need to adapt to the changing demands of world football from the mid-2000s. In reality, this conclusion would be slightly misleading.

Okocha | Ill-suited for 4-4-2

The first signs of a shift came when Frenchman Philippe Troussier was appointed two games into the qualifiers for the World Cup of 1998. He had a clear vision of how he wanted to play: an unusual 3-5-2, which was occasionally 3-4-1-2, 3-1-4-2 and 3-5-1-1. This system enabled him to retain the threat of two strikers upfront, in addition to an extra man in midfield. He was summarily dismissed six months to the actual Mundial, and his experiment with him.

For the most part, however, the 4-4-2 persisted till only recently.

Stephen Keshi’s 4-3-3 (4-2-1-3) is the first real sustained shift away from the norm. The trouble has not been the system in itself, but the personnel available. As more and more club sides moved away from a two man midfield, the skill set required to play on the flank changed. Where there was once an emphasis on hugging the touchline and good crossing ability, there is now a greater demand for smart movement, passing and shooting.

The out-and-out winger is an endangered species.

Nigeria has simply stopped producing top level wingers. Where there once was Emmanuel Amuneke and Garba Lawal (hardly a flying winger himself), there is now Victor Moses: a speedy dribbler who likes to drift and roam around the pitch creating overloads. In place of Finidi George and Tijani Babangida, Ahmed Musa’s name is stencilled on the door; the CSKA Moscow man plays upfront for his Russian club, and was prolific in his youth career as a forward.

So, would the Super Eagles benefit from a return to the 4-4-2 of yesteryear?

Atletico Madrid, the big success story of Europe in 2013/14, have shown that with the right execution, stringent organization and fierce combativeness, the system can be successful. However, Diego Simeone’s side plays extremely narrow, with the wide positions taken up by hardworking midfielders rather than wingers: Arda Turan is a no. 10, Koke is a central midfielder; and attacking width is supplied by overlapping fullbacks.

The top teams are those who maximize innovation and stay in touch with tactical advancement. However, truly great teams are those with a sense of personal conviction, which are unafraid to impose their own style and force others to adapt to them. However, with the slow extinction of the old-fashioned winger, the wide 4-4-2 that ‘uses the wings’ is unlikely to rear its head again any time soon.

It will, however, remain the idyll of Nigeria’s footballing soul.

No comments:

Post a Comment