Appointed in 1996 to much scepticism as an unknown to

British fans and players, taking charge in what seemed like chaos, the

Frenchman quickly set right those who doubted him

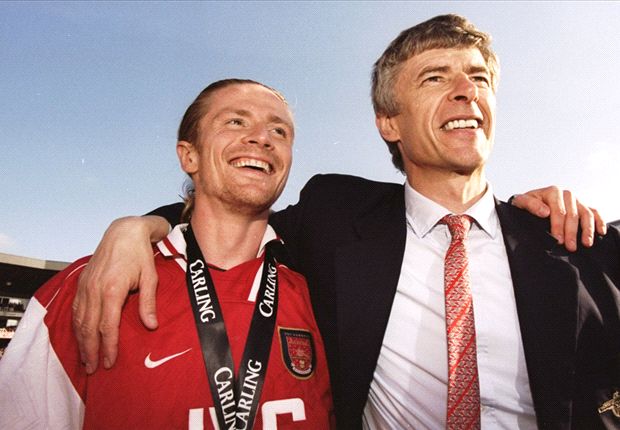

As Arsene Wenger ponders his 1000th Arsenal team selection for Saturday's crucial clash with Chelsea, it is sobering to think that only people over 20 years old can remember anyone other than the Frenchman managing the Gunners.

Wenger's tenure at Arsenal, now halfway through its 18th year, spans 17 top-four finishes, 16 consecutive Champions League campaigns, one unbeaten league season, two doubles, three Premier League titles, four FA Cup triumphs, six Community Shield appearances, 572 victories (for a win percentage of 57.3), innumerable club records and countless scintillating performances by a host of players whose careers blossomed under his guidance.

He has become synonymous with the club, their move from Highbury to the Emirates Stadium, their brand of passing football - and both the accumulation of trophies early in his reign and the lack of silverware in more recent years. Yet, with Arsenal currently hovering between renewed glory and repeated failure to land a prize, their fans are divided between those who still trust Wenger to deliver and those who have lost patience with his methods.

Neither side, though, has recent experience of what supporters of every other English league club have gone through since 1996: managerial change. So what were the circumstances when last the Arsenal board appointed a new boss?

| THE ROAD TO ARSENAL | |

|

|

| WENGER'S CAREER PRE-GUNNERS | |

| NANCY (TROPHIES) MONACO (TROPHIES) GRAMPUS EIGHT (TROPHIES) |

1984-87 0 1987-94 2 1995-96 2 |

Many fans were therefore shocked when, on the eve of Rioch's second season, the board relieved him of his duties. He had, it was true, alienated some of the senior players (notably Ian Wright) and it emerged that he had not signed the contract that would have prolonged his tenure.

More pertinently, though, the board were no longer confident that Rioch was the man to lead Arsenal into a bold new future. The vision for that future was largely Dein's and he knew exactly who could fulfil it: an erudite Frenchman of whom very few others in the insular world of English football had even heard.

Dein had first met then-Monaco coach Wenger on January 1, 1990, at Highbury and the two became good friends over the following years, with the Arsenal director convinced that the Frenchman was the ideal boss for the Gunners. He had pushed for Wenger to get the job when Graham was sacked but the rest of the board had misgivings and appointed Rioch. Now they accepted Dein's recommendation.

There was initial hostility from a lot of fans. Many felt that Rioch had been hard done by and many more were dismayed by the timing of his dismissal, a mere five days before the team were due to kick off the 1996-97 campaign. After the newspapers had teased them by tipping Terry Venables or bookies' favourite Johan Cruyff to get the job, plenty were unimpressed when the hitherto-unknown Wenger was announced. "Arsene who?" mocked the Evening Standard's headline. As 'Fever Pitch' author Nick Hornby put it: "Trust Arsenal to appoint the boring one that you haven't heard of."

To compound the impression that the whole episode had been handled clumsily, Wenger was not even yet available to take up his new role. He was contracted to Japanese club Grampus Eight until January. That meant that Stewart Houston, No.2 under both Graham and Rioch, was handed his second stint as caretaker but Houston felt that he was ready to be somebody's No.1 and resigned in early September to accept such a role at QPR, ironically appointing Rioch as his assistant. Into the breach stepped long-time club servant Pat Rice until Wenger could get there. Things seemed to be bordering on the farcical.

The negative reactions were perhaps understandable. Arsenal were breaking the mould: apart from brief, ill-fated experiments with Dr Josef Venglos and the 'anglicised' Osvaldo Ardiles by Aston Villa and Tottenham, respectively, there was little experience of foreign managers in English football and no precedent of success - though, within eight months, Ruud Gullit would guide Chelsea to FA Cup glory in his first season as player-manager and so become the first non-British boss to win a major trophy in England.

Even Wenger has acknowledged that "you needed to be a little bit crazy to do what Arsenal did" in appointing him. He told The Guardian: "They were crazy in the sense that I had no name, I was foreign, there was no history. They needed to be, maybe not crazy, but brave. I can show some articles where people tried to prove that foreign managers can never win an English championship."

By the time that news came from Nagoya that Wenger was being released from his contract early and would officially take the reins at Highbury on October 1, intrigued Arsenal fans had discovered that the incoming manager boasted an impressive CV, having won trophies in France and Japan. He had also built a reputation for spotting talented youngsters and developing them into key members of teams who played with flair and panache.

So Wenger, when he was finally unveiled, had to deny lurid rumours and defend himself to a media scrum that had gathered on the steps outside Highbury's marble halls. At that point he must have wondered exactly what he was stepping into but dealt with it calmly and authoritatively and got down to business.

He had already made a start, several weeks before his arrival, when he advised the board to sign two French players, Remi Garde and Patrick Vieira. "I had to be quick because he was on the verge of signing for Ajax," Wenger later said of Vieira, adding: "I intercepted him when he was in Holland."

Fans got their first evidence of his ability to identify and recruit future stars for modest fees when Vieira made a sensational debut, coming off the bench in a 4-1 victory over Sheffield Wednesday when Rice was still in charge. Garde's impact would be less explosive but Gooners soon learned to trust Wenger's judgement in the transfer market as the likes of Nicolas Anelka, Emmanuel Petit, Marc Overmars, Freddie Ljungberg, Thierry Henry, Lauren, Robert Pires, Kolo Toure, Robin van Persie, Cesc Fabregas and others who arrived with little or no profile in English football proceeded to become club legends.

These overseas players were all receptive to Wenger's methods, training and tactics but the new boss also revealed a perceptive and flexible side by winning over and prolonging the successful careers of the English core around which Graham's winning team had been built.

Again, he had to overcome initial suspicion and scepticism. When Dein had addressed the squad at their old training ground after Rioch's departure and sought to reassure them that the club had a top-class replacement lined up in Wenger, a voice at the back responded: "Who the **** is he?"

| WENGER'S 1000TH GAME SPORTMASTA'S COVERAGE IN FULL | ||||

|

||||

| 1000 GAMES LATER: ARSENAL THEN & NOW | ||||

| WENGER REJECTED £1M PAY HIKE | ||||

| THE MAN WHO REINVENTED THE ARSENAL WAY | ||||

| WENGER'S BEST AND WORST SIGNINGS |

Nor did multilingual engineering and economics graduate Wenger inspire immediate confidence in England right-back Lee Dixon, who unflatteringly likened him to Inspector Clouseau. His full-back partner, Nigel Winterburn, was apprehensive and felt that his position would be under threat as the new manager had revolutionary ideas about training and nutrition. "There were a lot of rumours swirling around that he was advised to get rid of the back four," Winterburn recently told the Daily Mail.

But Wenger was open-minded, listened to what Arsenal insiders had to say about the iconic defence and was prepared to compromise. Winterburn believes that he was impressed when he saw the players' ability and desire in training, recalling: "The training was good. It was sharp, it was energetic, it was different." The Frenchman encouraged the players to express themselves more and be more willing to improvise. They responded positively.

They were less enthusiastic about the dietary changes upon which Wenger insisted. Fish, white meat, steamed vegetables, mineral water and pasta swiftly replaced confectionery, fast food and alcohol. There was a hint of rebellion against what they termed the 'Evian-broccoli diet' when the players chanted "we want our Mars bars back" on the team coach to an early match.

But Wenger was never going to compromise on that and the players accepted the new regime when they started to feel the benefits. As Paul Merson famously observed later that first season: "The new manager has given us unbelievable belief."

Meanwhile, rivals such as Alex Ferguson, who had derided Wenger shortly after his arrival, querying what this Frenchman could possibly know about "our game", would quickly find out. So would those journalists who questioned what benefits a foreign coach could bring to English football. The Observer's Jon Henderson had written disparagingly in August 1996, prompted by Wenger's imminent arrival: "Those few who have tried to transform the manly virtues of our national game into something more aesthetic have tended to disappear up their own intricacies while their teams have disappeared down the table."

Yet, by the end of his first full season in charge, Wenger had led Arsenal to the double, becoming the first foreign-born manager to win England's top flight. Now, in 2014, he remains in his post, still in contention for the title and the FA Cup, his continuous tenure at one club now by a distance the longest among current managers in English league football.

He is Arsenal's longest-serving manager by a margin of almost five years and has been in charge for some 460 more matches than the second, Bertie Mee. Given that 460 is also the number of Arsenal games that George Graham oversaw, Wenger's longevity has been remarkable and, while he has won more major honours than any of his predecessors, he has also given Arsenal fans some of the most exhilarating football that they have ever seen.

Who could possibly have predicted that back in 1996?

No comments:

Post a Comment